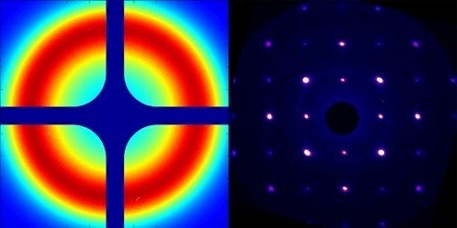

The left side of the figure shows the pattern of the x-rays appearing on the receiver after passing through the iron-platinum nanoparticle sample, and the right is the pattern of the electrons appearing on the receiver after passing through the iron-platinum nanoparticle sample. The x-ray data reveals the magnetic state information of the sample, and the electronic data provides atomic structure information. Image source: Alexander Reid/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

The SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is part of the Department of Energy, and scientists at the lab saw for the first time that atoms in iron-platinum nanoparticles, a new generation of materials used in magnetic data storage devices, react extremely rapidly to transient laser flashes. the process of. Research on these basic motion processes may lead to discovering new ways to manipulate and control the illumination of these devices.

The reason for seeing this process is the use of two world-leading instruments – the “camera†Linak Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser and ultrafast electron diffractometer (UED) with ultra-fast atomic resolution. ). The team showed that laser scintillation demagnetizes the iron-platinum particles in less than one trillionth of a second, causing the atoms in the material to move closer in one direction and away from each other in the other.

The results also provide a first atomic description of the magnetostrictive mechanical strain, magnetostriction, which occurs in magnetic materials as magnetization changes. This phenomenon is manifested in many ways, including the electrical hum of the transformer. The study has been published in the journal Nature Communications, where researchers have previously considered these structural changes to be relatively slow. However, new data suggests that ultrafast processes can play an important role.

The study was conducted by SLAC and Stanford, and Hermann Dürr, Principal Investigator of the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SMES), said: "The previous iron-platinum nanoparticle performance model did not consider these extremely fast and basic atomic motions. We don't yet understand the full impact of these processes, and computing, including them, may open up new avenues for future data storage technologies."

Breaking through the limits of magnetic data storage

Magnetic storage devices are widely used to record information generated in almost all areas of the digital world, and they are believed to remain a critical data storage path for the foreseeable future. In the face of growing global data volumes, hardware engineers are working to maximize the use of these media to store information.

However, current technology is approaching its limits. For example, today's hard drives can achieve hundreds of billions of storage densities per square inch, and similar future devices are not expected to exceed one trillion bits per square inch. Therefore, new developments are urgently needed to take magnetic data storage to the next level.

Eric Fullerton, director of the Center for Memory and Records Research at the University of California, San Diego, said one of the co-authors of the new study: "The use of nanoparticle materials such as iron-platinum for hard-assisted magnetic recording in hard drives is a promising approach. In this method, the information is encoded by nano-focusing lasers and magnetic fields, and may even only require lasers, thereby changing the magnetization of the nanoparticles. These new generation hard disks can have greater storage density and are already industrially available. Tested and may be available soon."

This study by SLAC explores an important aspect of this technology - the interaction of lasers with iron-platinum nanoparticles.

X-ray combined with electron

The researchers first placed nanoparticles of about 50 atoms in diameter into a Linak Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser. The laser then illuminates a brief optical laser pulse. With LCLS' super bright femtosecond X-ray flash, they are able to follow the laser to change the magnetization state of the material - from full magnetization to substantially demagnetization. A femtosecond is one millionth of a second.

They repeated the experiment using a UED instrument on the SLAC Accelerator Structure Test Area (ASTA) to detect samples with high energy electron pulses. In this way, the scientists made a stop motion movie about how the nanoparticles move after being hit by a laser.

Alexander Reid, the first author of SIMES and LCLS, said: "Only by the combination of these two methods, we can see the full picture of the laser ultrafast atomic reaction. The laser pulse changes the magnetization in the material, which in turn drives the structural change. Cause mechanical strain."

Wang Xijie, head of the SLAC UED project, said: "This study proves how powerful these two methods are. The absolute key to determining the three-dimensional atomic motion is the high-energy electron beam. Without x-rays, we cannot relate these motions to the magnetic behavior of the material. stand up.

In addition to researchers at SLAC and Stanford, the collaboration includes scientists from the Czech Republic, Germany, Japan, Sweden, the Netherlands, and scientists from several US institutions. Part of this research was supported by the DOE Science Office and the Laboratory-directed Research and Development Program (LDRD). LCLS is a scientific user facility for the DOE office.

Pneumatic valve is a kind of valve controlled by air pressure, which is widely used in industrial automation control system. Its main applications include the following aspects:

1. Fluid control: pneumatic valve can be used to control the flow and direction of liquid or gas, such as controlling the flow in the pipeline, exhaust gas emission, etc.

2. Pressure control: pneumatic valve can be used to control the pressure of fluid, such as controlling the pressure of compressed air, regulating the pressure in the hydraulic system, etc.

3. Temperature control: pneumatic valve can be used to control the temperature of fluid, such as the temperature of heating or cooling system.

4. Automatic control: pneumatic valve can be linked with sensors, PLC and other equipment to realize automatic control, such as automatic production lines, robots, etc.

5. Safety control: pneumatic valve can be used for safety control, such as controlling emergency stop, preventing overload, etc.

In general, pneumatic valve plays an important role in industrial automation control system, which can improve production efficiency, reduce costs, and ensure safety.

Pneumatic Valve,Pneumatic Valve Types,Pneumatic Control Valve,Pneumatic Actuator Valve

WUXI KVC-VALVE , https://www.kvgatevalve.com